TRANSACTION SECURITY SERVICE

TRANSPARENCY ALONG THE VALUE CHAIN

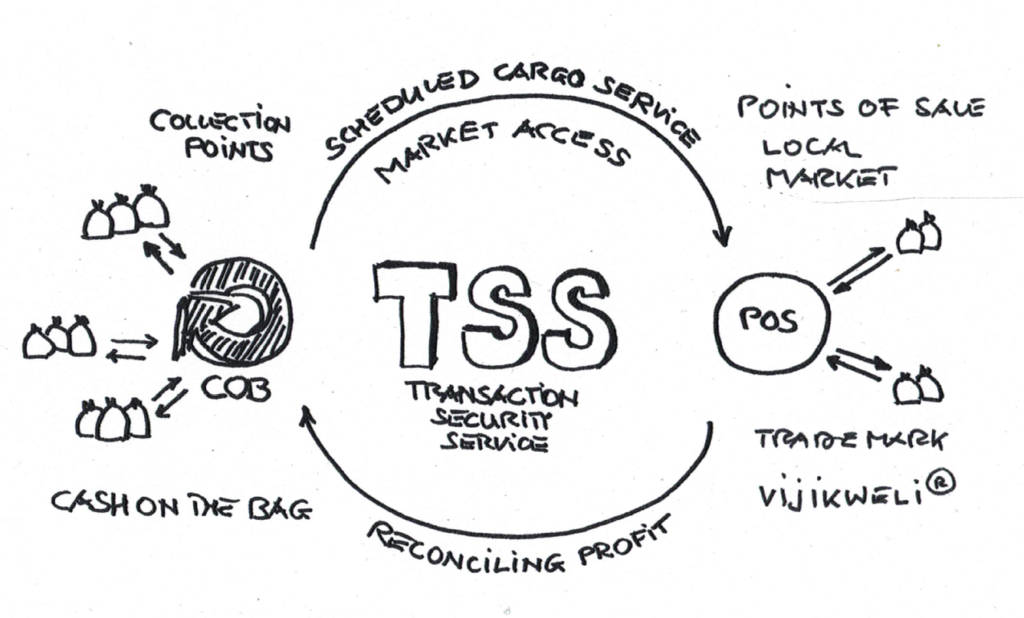

2018-12-14. TSS – Transaction Security Services – is the business model of TBM. TBM offers TSS to farmers and to end consumers, and to all actors along the chain between the two.

TBM provides the controls that achieve complete financial and operational transparency. All actors in a deal can rely on each other because in case something goes wrong, TBM will know what happened, where it happened, who is responsible and who therefore must rectify. This creates trust and therefore higher efficiency along the chain. This higher efficiency results in higher income to farmers, and that higher income justifies the commission which TBM charges on the net profits farmers make.

A typical TSS deal works like this:

- TBM helps farmers find good buyers.

- When buyers and farmers agree on prices, they ask TBM to take the deal through.

- When farmers deliver at agreed times to agreed collection points, TBM does all the quality checking. TBM then pays the farmers an advance for the approved and accepted produce they delivered. Usually this is on-the-spot payments. We call it “Cash-on-the-bag” (COB). The produce still belongs to farmers. How much each farmer delivered and how much advance s/he was paid TBM individually tracks for each farmer. This is what we call the “collection loop”.

- TBM then organizes all the operations between collection point to delivery to the final buyers, eg. cleaning, grading, packaging, processing, stocking, transport, distribution to outlets, etc. TBM looks for the best operators and pays for these services on behalf of the farmers. We call these the middle costs.

- We aim to take a produce up to the many final buyers in town. That means TBM also takes care of distribution to many small retailers who sell in small quantities to end consumers. We call it the distribution loop. Like this we allow farmers and TBM to also together earn the added value of processing and distribution. We also say we aim for “double-loop deals”, ie. collection loop and distribution loop.

- The buyers pay the price agreed with farmers to TBM. TBM then puts this money into the clearing account of the deal.

- From the clearing account TBM then recovers all the middle costs.

- What is left is shared between farmers and TBM, usually 90% farmers and 10% TBM. With this commission TBM pays for its staff and operations that are not specific to any deal, and for its own profit.

- From the share of the farmers, TBM then recovers the advance payments in point 3, including interests in order to cover the credits that may have been required to make those advance payments.

- Any remaining money in the clearing account is then bonus to farmers. TBM pays out to each farmer his or her share of the bonus, based on the individual tracking of delivered amounts and paid advances.

- Finalization of a deal happens when all money movements have been done. TBM then calls all farmers who delivered for the deal and explains the complete calculations in the clearing account, particularly the middle costs. This is often very interesting for farmers, because they can see where they may earn themselves additional income by avoiding certain middle costs (eg. in cleaning and drying, in packaging, in transport, etc).

The effect of TSS is usually only understood by farmers who have experienced how it feels to be paid a bonus. That is when they get really interested in how this works. They then realize that:

- They are the owners of the produce until sale to the intended end-buyer.

- They have a possibility of increasing their incomes by avoiding middle costs.

- TBMs income is tied directly to their own income. Therefore both TBM and farmers have the same interest in looking for the best price, and reducing middle costs as much as possible. TBM therefore is on their side in negotiations for transactions along the whole chain.

- The risk of deterioration of market price while produce is in transit or with unreliable buyers who don’t pay or pay late etc, or with unreliable toll-processors, is with TBM. This risk is acceptable for TBM because it is the expertise of TBM to avoid such risks as well as possible. The justification of the commission is this risk for TBM.

The effect of TSS on buyers is that they can rely on regularly getting the produce they need at quality standards that they indicated.

The effect on processors and transporters is that they can use their resources for improving their services instead of using their money to bear the risk of purchasing and selling produce along the chain.

TBM operates its own network of agents both at village level (collection points) as well as in cities (distribution points). These agents are not employed, they take a share in the commission. That way all TBM staff are incentivized to achieve a good selling price and reduce the middle costs, and that is exactly in line with the interests of farmers themselves. This makes transparency and building of trust along the chain easier.

The effect of TSS is the win-win-win-win-win:

- WIN for farmers who can participate in any value-addition after delivery of their produce.

- WIN for TBM. ie. the commission tied to the financial success of farmers.

- WIN for actors along the chain who can concentrate their efforts and capacities on providing good services instead of worrying about buying and selling produce

- WIN for final buyers because they are sure of quality and delivery

- WIN for all because all can be sure that if something goes wrong there is no need to quarrel: TBM will know what happened, why it happened, and therefore who needs to do what in order to rectify. And of course: TBM can provide lessons for all actors about how to improve efficiency and security in their transactions along the chain.

Challenges for TBM to expand:

- Of course financial resources are required to push ahead with deals, eg. for paying the COB-advances for deals. With present banking conditions in Tanzania this is almost impossible.

- The even bigger challenge is the need for training and learning on-the-job by a wide range of actors, starting with its own TSS-agents, and adding in processors and transporters, etc. This takes time and also costs considerably. The present start-up operations of TBM do not earn enough money to allow to invest much here, so growth can only be slow.

History of the TSS-concept and its implementation

2021-10-18. Status-Notes based on research and discussions between Eli-Bahat-Ueli.

IFAD-funded projects began to attempt to improve market access for small holder farmers in East Africa. This started around 2004 and gradually stopped around 2017. Bahat Tweve was involved in the early stages as “Mkulima shushushu” (Farmer spy) in those parts of IFAD-projects implemented in the southern highlands of Tanzania. His job was to explore the real prices in the markets and convey that information to farmer groups formed by the projects. Over time Bahat was networked by the IFAD-efforts with other actors in Kenya and Uganda, who exchanged on how to improve market access for small-holder farmers. It soon emerged that there was a difference between those actors in the exchange network who worked for NGOs or consulting companies contracted by the projects to implement efforts, and those actors who themselves were commercially active as entrepreneurs. Bahat belonged to the commercially oriented entrepreneurs.

Over a period of about 3 years the concept of Transaction Security Services (TSS) emerged among the commercially active entrepreneurs in the network. Bahat was one of the most important sources of ideas for this. Still in the framework of IFAD-projects various efforts were undertaken to develop and implement TSS in an action-research kind of procedure. This was effectively facilitated by Rural African Ventures Investments, a company contracted by IFAD in the various phases to mentor the learning peer-exchange among the East African actors in developing TSS. Ueli Scheuermeier and Clive Lightfoot of RAVI were both involved throughout this IFAD-period as consultants to IFAD. During this time several actors launched their companies to manage TSS. In Tanzania Bahat launched Tanzania Biashara Mapema (TBM) as a commercial company with TSS as its business model.

With the decline of the programs of IFAD the various companies in Kenya and Uganda dropped TSS as their business model and closed or migrated to other businesses (eg. food-processing in Uganda). Also, with the end of IFAD-programs also RAVI declined and finally closed. Ueli Scheuermeier however remained in close contact with Bahat, who continued to further work with TSS and try to operate it commercially, even after all project funding had stopped. This was also the time when Bahat suggested to Ueli, that it was now time to forget about projects and consulting and to rather engage in a business relationship.

It was against this background that the concept of farip emerged, a Swiss foundation that interacts with African rural innovators in entirely commercial ways, ie. as something like venture capitalists and angel investors, but adapted to the challenges of low-income rural innovators with often poor skills in financial transactions or business documentation. With the emergence of farip acting as a regular longterm investor in TBM, TSS was again central in the further conceptual efforts. Most importantly the combination of metal silos for grain storage at the farm and TSS-deals with its COB-fund was worked out, and more recently the Scheduled Cargo Services and BOP-outlets (see separate status notes on both).

TSS has therefore remained the core of the business model of TBM, and further attachments were made (ie. metal silos, COB-fund, SCS, BOP) to enhance TSS. This was necessary in order to manage the complex challenges. TSS must therefore be seen as a complex set of interacting businesses that make direct and transparent and therefore trusted market access for small farmers possible and make safe food available to the big majority of low-income dwellers in the cities.

Present working system

1. If we forget about COB and silos, it is the same like before:

- What buyer pays, minus all middlecosts and minus interest on COB = net profit

- Of the net profit 90% is for farmers and 10% is for TBM as commission to cover all costs of TBM and commissions to agents, etc.

- If there is bonus, TBM pays bonus to farmers

- Transparent tracking and documents allow to explain to each single farmer how her or his money is calculated.

2. Farmers often need cash during harvest time and cannot afford to clean and store their crop. That is why we introduced COB. It is deducted again when paying farmers. Also the interest is deducted as another middle cost. This one remains the same.

3. But this is new: After payment of full COB-price, the crop belongs to TBM, not to the farmers. It means TBM decides when to sell the crop and to which buyer to sell. When TBM needs the crop to sell to a buyer, TBM can go to the farmer and take the crop and transport it to the collection point. TBM pays for transport to collection point.

4. If a farmer only needs small amount of COB to solve his problems, s/he can request smaller COB-advance. Example: If the price of the crop in the silo is total 400’000, s/he can request to only get 150’000. So if TBM needs maize, TBM can only come and get maize for the 150’000. Of course in that case the farmer can decide to also contribute the other part, or to keep it for hunger emergency.

5. The silos remain in the ownership of TBM. However, TBM encourages farmers to buy silos for keeping for their home-consumption.

6. The reason why farmers can be interested to keep the crop, which belongs to TBM, in silos in their home is this: In case there is still crop in the silo which belongs to TBM, but the family is running out of food, TBM will sell back the crop to the family at original COB-costs, plus the interest for the COB.

7. Farmers can refuse to keep the crop in silos in their house. In that case TBM will take the crop and store it in silos at the collection center. When TBM is selling, it will first sell that crop which is at the collection center.

8. TBM also must organize and run collection centers. These are places where TBM can put own silos to make ready for showing buyers. At the collection center TBM will also organize any grading, drying and cleaning. The costs for grading/drying/cleaning are middle costs which are calculated separately for each farmer.

9. Farmers can also agree not to sell to TBM but to store maize in silos. In that case they work with TBM like normal TSS. It means when TBM finds a buyer, they can contribute to the sale and they get full payments according to TSS-calculations.

10. Maize in silos that belong to TBM must be marketed through TBM.

11. TBM wants to keep only about 50 silos at the collection center, which is just more than 30tons for filling a semitrailer-truck. That way any buyer can inspect the crop at the collection center and buy it. After buying, immediately TBM will get more maize from other farmers for again topping up to full capacity at the collection center.

2021-10-18